On Creative Practice

My father's first studio was the laundry, with the rifles for roo shooting hanging on the wall, an old-fashioned meat mincer clamped to the bench and his sloping desk squashed against the door to outside. Often, bored during the school holidays, I sat on the washing machine and watched him paint. Once we looked through the windows to see Mum, who had just woken from a nap, yawning as she pulled out weeds near the tankstand. I, who must have been 6 or so, asked, 'How can she be tired if she's just had a sleep?' Dad replied, 'She's still waking up.' I found this an unscientific and unsatisfactory answer, but even then I sensed my father's moods and knew when a conversation wouldn't continue.

A few years later Dad built his own studio, and H and I would often go there after dinner to draw on the discarded pieces of cardboard from which he cut his mounts. Dad played LPs and tapes from musicals as he painted. H drew cartoons which he cut out and stuck on the wall in our bedroom next to his Halley's Comet poster. As with my piano playing, I became technically proficient and was able to copy anything, but I lacked H's imagination and flair.

My sister, brother and I all studied art at school, and later Dad left the farm to teach art himself, littering the house with art books and study notes. It was because of this education — formal and informal — that I was able to recognise the community of artists featured in Alex Miller's new novel, Autumn Laing, as being loosely based upon the Modernists at Heide. As I lay on my red velvet couch reading, I thought I was in for an exciting ride. However, as I turned the pages, I became increasingly disappointed by the lack of momentum and dull writing, and found myself skimming the text, which I rarely do. There was an absence of detail grounding the work and, breaking the most fundamental rule in the writing book, far too much 'telling' over 'showing'.

The novel is the memoir of Autumn Laing, written, she says, to put Edith, the wife of her lover Pat Donlon, back into the picture, to 'give her portrait the first place in this testament' (21). While attention is paid to Edith at first, the work is overtaken by Autumn's focus on Pat Donlon, relegating Edith and her art to the margins as she had been all along.

After Miller's perfectly pitched Lovesong, with its delicate rendition of how a woman's desperation for a child eroded a relationship, the depiction of infertility in this work was a caricature. Following 'a period of aggressive and exaggerated sexual behaviour' in her late teens (178), Autumn is unable to have children. When she finds that Pat Donlon is to father a child with Edith, her reaction is to knock over her wine glass and slam the door, while 'a moment later her wail came from the deep night, “I hate men!”' (210). Continuing in this hyperbolic vein, Autumn's carers, a nurse and her biographer Adeli, have breasts like 'great melons diving about like bloated water bombs' (185) and 'trembling balloons of naked flesh' (187), an unsubtle affront to Autumn's angularity and infertility.

Each of these complaints could of course be explained by the voice and biases of Autumn, but a writer who has published his tenth novel should be capable of shaping better sentences than 'I hated him. I wanted him to make love to me. To lose himself in a wild torment of passion for me' (369). Mills and Boon territory, indeed.

Aside from allowing me to recognise the loose skeleton upon which Autumn Laing hung, my father's creative practice has been instrumental in showing me how to become, and to live, as an artist. Although he doesn't have the all-consuming passion and ambition that I do (for he would, ultimately, prefer to be renovating houses than painting), his art does seem to tug at him the same way that writing never leaves me alone.

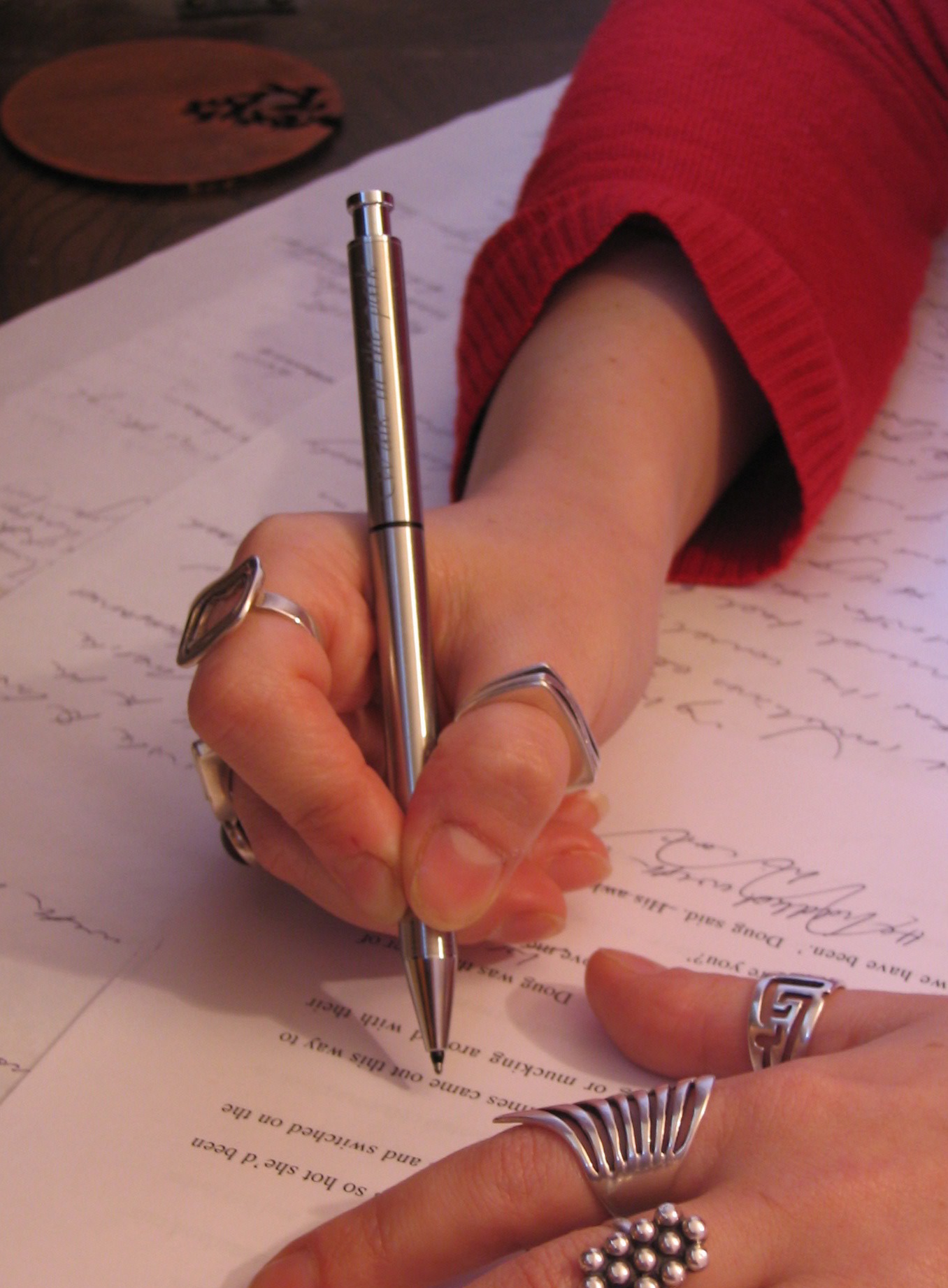

At home for Christmas, when he was painting and I was writing, we came out for coffee (or rather, he heard me in the kitchen and came out for someone to talk to).

'It's so boring,' he complained. 'Why do we do it?'

'Because it's a vocation,' I replied.

The word comes from the Latin word vocare, meaning 'to call'. It's a voice you can't ignore. Certainly, if I don't write, I start to feel a bit shitty and ill, and other writers I have spoken to feel this way as well.

Dad also taught me the importance of a single-minded dedication to a cause. His father once said to him, 'There's no such word as can't', and he relayed this to me in turn as I was growing up, as he did the phrase, 'If at first you don't succeed, try, try again.' For a stubborn little girl who always wanted to be the best but was sometimes thwarted by a disability, these mantras helped drive me on. Even now, when I despair that my friends have houses and cars and I am walking away from the white picket fences and down the dusty road to post yet another grant application, I remind myself that I can never lose faith in my capacity to succeed. To do so would be to give up my raison d'être.

In a piece of poetic dovetailing, my father's art supports my own, for my parents help to put a roof over my head so that I can work part-time and keep writing. Likewise, my childhood on the property he worked with his brothers has given rise to almost all my themes, and the character of the artist/farmer has appeared in at least one short story, and will feature in novel #6.

Dad's paintings are available here. If you're stuck for gifts for weddings, birthdays or generally esoteric occasions, these will fit the bill. Plus Mum keeps at him to clean out his drawers, so divesting them of paintings is always helpful for household harmony.