Review of Mazin Grace

Chapter One of Mazin Grace is titled ‘Minya wunyi wonganyi’, the Kokatha words for ‘small girl talking’. The small girl is Grace Dawn, and the opening of her narrative signals that this is a novel about naming and identity:

My name is Grace. Grace Dawn. That’s ‘cause I was born just as the jindu came up over our Kokatha country on Koonibba Mission. Papa Neddy gave me my name. Said if it’s good enough for Superintendent to call ‘is girls Charity and Hope, it was good enough for me to ‘ave a Bible name too.

The first three sentences tie Grace’s language to the place she was born: jindu(Kokatha for ‘sun’), Kokatha country, and Koonibba Mission, and the influence of the mission and her Indigenous culture is mirrored in her language, a mixture of English and Kokatha, which in turn reflects who she is: an Indigenous girl raised on a mission, trying to find out the identity of her father.

To begin Mazin Grace is to be thrust into the wide circle of Grace’s family. I found trying to negotiate the family relationships, at the same time as reading the language - which incorporates Kokatha words - to be confusing at first, but at the same time I liked it, as it reminded me of my own incredibly loud family – whenever my sister comes home at Christmas, there are dogs barking and kids yelling, while she shouts over the top of everyone, with expansive arm gestures. When things calm down, I can finally figure out what’s going on. When I persisted with this book, and adjusted to flicking back to check the list of Kokatha words, I came to love the rhythm of Grace’s sentences. I eventually learned enough of the words to read easily, which seemed to me a lovely way to get to know a culture, that is, through a novel.

The mix of languages also indicates Grace’s protection of her Indigenous culture amidst the strictures of the Mission: ‘Sometimes, we say lotta things quiet-way to each other without opening our mouth and they don’t know what we sayin’. We gotta talk like that sometimes, ‘cause them walbiya mooga [white people] on the Mission won’t let us use Kokatha wonga either. We gotta talk English’ (9). At other times they use sign or body language, and this strategy, of talking ‘safe-way’, is even more important when the ‘welfare mob’ (10) come, because it helps them to talk without being heard. Indigenous language isn’t just a means of communicating, but a way of surviving.

This isn’t a plot driven work, but rather revolves around Grace’s journey from child to young woman, and her search for her father. Being fairer than other kids in the mission, she is taunted for her skin, which this makes her feel ashamed, as she says, ‘I can’t scrape the whiteness outa me. I can’t scrape out that shame of who I am’ (228). I was surprised that there was racism within the community itself, but I could empathise with this sense of being neither one thing nor another as, not being completely deaf, I belong to neither the worlds of the hearing or the deaf.

Grace is a spirited character who frequently gets into trouble for speaking her mind, and I liked her independence. This attribute becomes important later on when holds the family together when they run out of money and food. By the time she heads off to school in Adelaide at the end of the novel, you know she’s going to be okay.

The novel is a fictional account of Coleman’s mother’s childhood at the Koonibba Lutheran Mission in the 1940s and 50s. The Author’s Note at the end describes how Coleman came to write the novel, and the way in which she chose to write it, and I think it’s worth buying the book for this account alone. It’s describes the devastating impact that colonialism has had upon Indigenous people, and how writing the novel was part of the healing process for Coleman’s mother, who was ‘able to reclaim a little bit of my past that has been denied me’ (242).

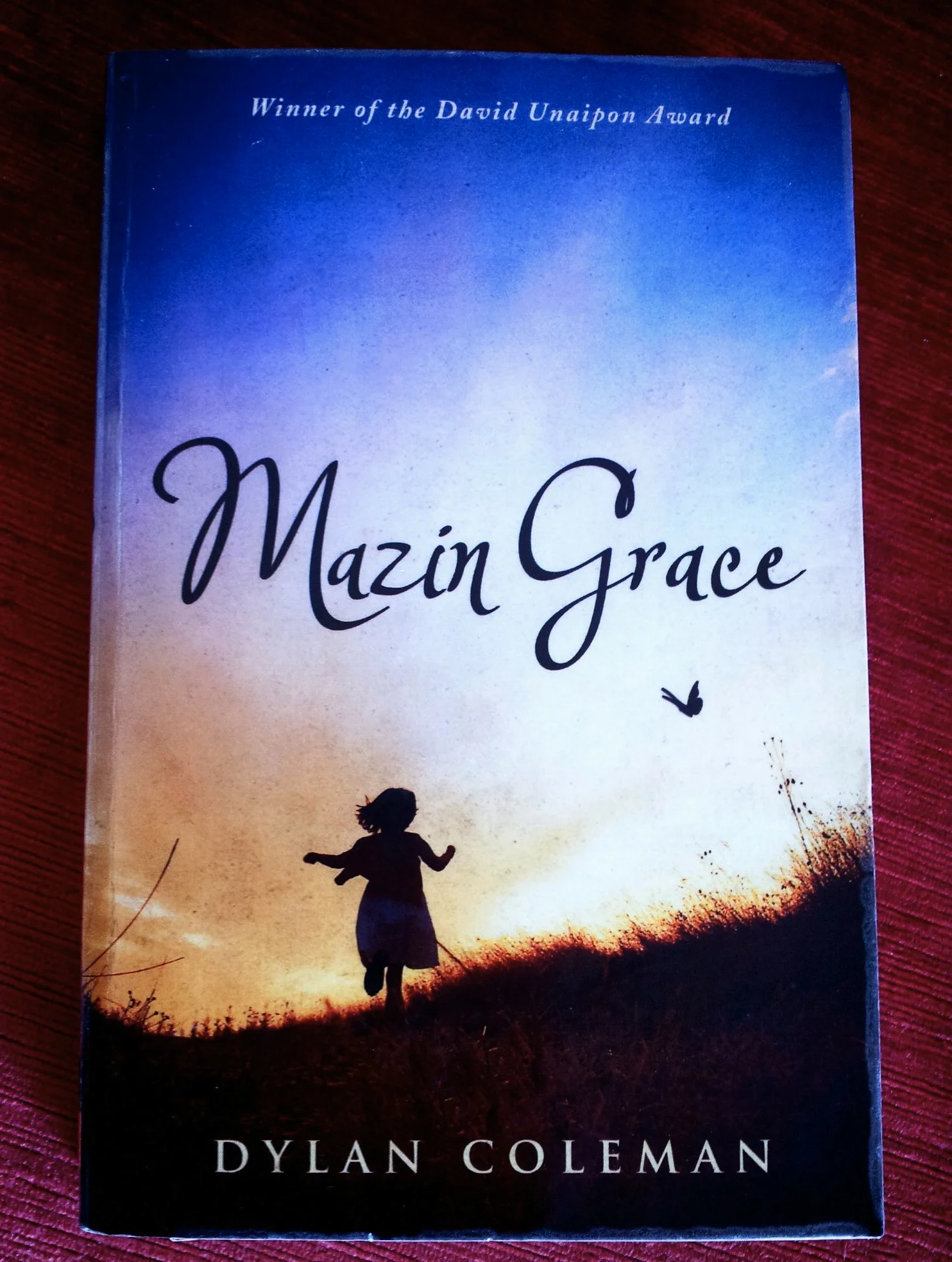

This makes it saddening to read Coleman’s thanks, in the Acknowledgements, to those who make the Queensland Premier’s Literary Awards possible. Mazin Grace was the winner of the David Unaipon Award for an unpublished manuscript by an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander writer in 2011. ‘Without this award, Grace’s voice may not have been heard’, Coleman writes. Campbell Newman canned these awards as one of his first acts as Queensland Premier in 2012, which indicates his disinterest in hearing the voices of writers. As Anna Funder, author of All That I Am, said of his actions: ‘I have spent my professional life studying totalitarian regimes and the brave people who speak out against them … And the first thing that someone with dictatorial inclinations does is to silence the writers and the journalists.’ Fortunately, the University of Queensland press was committed to retaining the David Unaipon Award, and with the help of some dedicated Queenslanders, the Queensland Literary Awards was formed. The recently announced winner of the David Unaipon Award for this year was Ellen van Nerveen for Heat and Light. Judging by the readings of her work that I’ve heard at Avid Reader, her book will be a stunner.

Book details: Coleman, Dylan. Mazin Grace. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 2012.

Borrowed from Brisbane City Council Library.

This is my 12th review for the Australian Women Writers Challenge.