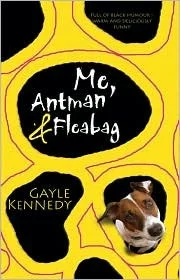

Review of Me, Antman and Fleabag

After reading the first page of Gayle Kennedy’s Me, Antman and Fleabag, you know you’re in the hands of a born storyteller. The narrator’s voice is distinctive and entertaining, with plenty of swearing – I loved it! After being told off too many time at the local park by rigid policemen, she, Antman & their dog Fleabag ‘stay home and party in a yard the size of an old hanky with trains roarin by every time ya favourite song comes on’ (1). They consult their lawyer cousin who explains that they’re doing the park scene the wrong way. He tells them to wash Fleabag and takes them to a ‘deadly park right on the harbour’ (2) near his place in Balmain. The dog gets on with other dogs in the park like a house on fire, ‘but that’s okay cos he got his nuts cut out a couple of years ago so he don’t go bluin no more’ (2). I was reading this on the bus, and started laughing.

The book is composed of a series of vivid vignettes. They revolve around people whom the narrator and Antman meet, and these characters are deftly drawn. Mrs Howard, a drunk, has scaly skin. When she picks it, ‘the flakes are layin all around her. It looks just like ashes after a bush fire’ (8). Meanwhile, little nephew Bunting, born in the middle of a drought, freaks out when he finally sees rain and gets into ‘such a state he’s almost stopped breathin’ (105). There’s also a heavy dose of irony throughout, which reminded me of Vivienne Cleven’s Bitin’ Back. On that note, I loved the talking back to whites. At a music festival, at which the narrator and Antman are the only Aborigines, even though it's a dreaming festival, a white man 'plonks himself down at our table and says, "Hello Aboriginal people." We look at im and say, "Hello Anglo man."' (69). I started laughing, again.

Amidst the humour, though, there is sadness. Grandfather, who fought in World War Two and won two rows of medals for service and bravery, wasn’t allowed to celebrate with his mates at the pub; he had to go round the back. And despite fighting for his country and being a Japanese POW, he had to ‘git a piece of paper to say he was good enough to go and git a job’ (62). It’s pretty painful, still, that there are amazing sportsmen like Adam Goodes on the field and people don’t think they’re good enough to play because they’re Aboriginal. Politicans like to bandy about the idea that Australia is the land of the ‘fair go’ but often it’s only a fair go for those who are white and male.

I identified with ‘Me, Antman and Fleabag hook up’, the story that Gayle read at the Accessible Arts conference last year. It’s about how the narrator was sent away from her family because she had polio, and when she came back her parents were strangers to her. It took them all a long time to get used to one another again. ‘For a long time I lived in two worlds,’ she writes. ‘One white, one black, and never really fitting into either’ (97). As someone neither completely hearing nor completely deaf, I often don’t feel like I belong anywhere either.

This book is a ball, but it’s important and serious too. It conveys the fun and laughter of families, but also the tragedy caused by colonisation. In a note at the beginning of the book, Gayle writes that the characters of the narrator, Antman and Fleabag 'were created for a story that won the NSW Writers Centre Inner City Life Short Story Competition. She liked them so much she wrote a book about them.' I loved these characters as well, as did the David Unaipon judges in 2006. If you read this book and get to know them, they'll win you over too.

This is my second review for the Australian Women Writers Challenge.