Review of Fishing in the Devonian

O’er November we leapt, and I didn’t get any blog posts down as I was madly tying things up before going travelling for a month for conferences, a writers festival & research. And now that I’m back I find that Christmas is less than a fortnight away and I have some nine reviews to write to meet the challenge I set myself for the Australian Women Writers Challenge. So, as usual, yours truly is hitting the panic button which will lead to an outpouring of creativity & thence a collapse in front of the Christmas tree, where the dog will find me and lick my face.

The festival was Quantum Words, a science writing festival organised by Jane McCredie, who also edited this year’s Best Australian Science Writing 2016 (a jolly good Christmas present for anyone still scratching their heads). I was on a panel titled How Science Made Me a Better Writer alongside poet Carol Jenkins and playwright James Saunders, chaired by the lovely novelist & journalist Ashley Hay. I spoke about the ecobiography I’m writing and how Georgiana Molloy was probably not only Western Australia’s first female scientist, but also its first female science writer. And I described how science makes me a better writer because it gives me fresh ideas and encourages precision and collaboration.

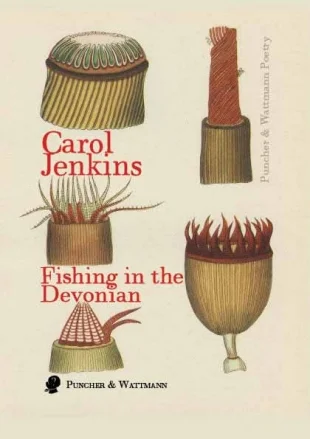

James described the TV programme he’s making about scientists and consciousness, which was fascinating (keep an eye out for it!) and Carol read out some of her poems. When I heard the latter, my toes began to tingle. Writing poems about science, she said, is way more interesting than writing about one’s cat or one’s ex. I agreed, and after the session I bought her second book of poems, Xn, and when I got home I ordered the first, Fishing in the Devonian.

The Devonian is a period of 60 million years, beginning at the end of the Silurian period some 400 million years ago. It’s named after Devon, in England, where the rocks from this period were first studied. It was an exciting period: plants began to stretch across land and grow into forests, evolving leaves and roots; the first seed-bearing plants appeared; the fins of the ancestors of tetrapods (four-legged creatures) evolved into legs and they began to walk on land; the oceans were increasingly populated with primitive sharks and placoderms (fish with armoured plates and pelvic fins, which gave rise to the limbs of the tetrapods) dominated watery environments. Fish in general became very diverse and the era was dubbed the ‘Age of Fish’.

Aptly, then, the first poem in the book is the titular ‘Fishing in the Devonian’ and aptly, Carol writes, ‘There is a lot/to think about in fishing in the Devonian’, including the contemplation of these life forms. You can sit in your boat and watch Tiktaalik rosae tempted by ‘the attractive ooze of mudflats/with morsels of scorpions and millipedes … trying its best to get out’ like its fellow fish, which ‘throng/up and over the shore on their lobed fins’. But, she humorously adds, be careful of the boat you use, for ‘spongey Devonian wood’ doesn’t have much by the way of ‘secondary thickening/through a stout source of carbon’ – the trees haven’t yet evolved to be strong enough!

It’s a charming poem to open with, and the poems that follow are similarly captivating. ‘A Life in Fridges’ describes fifteen fridges, capturing the arc of the narrator’s life from childhood to adulthood. As a child, she spent some time ‘opening the door to feel the engagement/and disengagement of the catch./ The term shut the door comes into/common parlance’. What child hasn’t been day absorbed in a fridge seal like this, especially on a summer’s day when the gust of cool air from the interior is so much more satisfying that a fan stirring hot air, and your mother tells you to stop wasting electricity? When she leaves home ‘someone’s old beer fridge/is dragged dripping, like adulthood/into the kitchen of McEvoy Ave’. This fridge is old and animated, it ‘coughs mechanically, a late/night shudder, as if dreaming it forgot how/to breathe and then the motor kicks back in/and gets on with it’. Then there is a baby and ‘the magnets come/the first twenty six/are the bloody alphabet which I pick up/about a thousand times a week’ and, finally, the markers of comfortable middle-age: ‘three kinds of yoghurt, five chutneys,/six varieties of soft cheese, a Tardis trail through dark matter,/time and meals’. It’s a clever way of telling a life; taking a quotidian object we never think about and investing it with personality, memory and attachment. The ending is so superb, and characteristically funny, that it’s worth quoting in full:

Outside is a public demonstration of family life;

of the inside, I say to visitors, don’t open that fridge,

it’s like my unconscious, there are good things in there

and some things you will not want to know.

To illustrate this, and that the term vegetable crisper

is an oxymoron, I gently lever up a liquid zucchini,

fizzing slightly yellow, photograph it and post this on the door. (51)

So yes, not all the poems are about science. Many are about childhood and growing up, sex, romance and women, one whom ‘throws herself/ – perfect body, less one breast – /off the cliff onto the rocks’ (How Much, p. 40) – and all of them, whether muted or bold – carry sensory detail that pulls the reader into another moment, then releases them.

I found only one poem to be clunky – ‘Kulin Seasons’ – a braiding of descriptions of the seasons described by the Kulin people and a series of events throughout the year advertising sales in stores. While some of the descriptions are delicate and gorgeous – witness ‘In kangaroo-apple season/you can watch small bats/harvesting insects from twilight’ – the author’s intent was too obvious, and it unsettled me.

And my favourite? Too hard to pick, but I loved these few lines from ‘Disorders of Belief’: ‘She wanted to believe in bone, muscle, blood,/skin and pheromones but ran into the anaesthetic/of romance, the predisposition to delusional/sexually receptive states’ (11), for what is romance but the swish of chemicals? And what are clouds, but symbols of inexpressibility, viz.:

I am photographing clouds, they are so hard

to talk to, carrying in an elegiac mass all the words

I didn’t say that were perfect for when we weren’t

lying together on a paisley cotton quilt, that

your great aunt, who bred silkworms, didn’t make. (‘Fifteen Tangents, p. 69).

Are clouds all that isn’t there? At any rate they are good metaphors for poems – we study their shapes and try to decode their meaning.

All this year I’ve been buying poetry books to compel myself to start writing poetry again, but I’ve been so busy & tired that I haven’t had time to do anything except get to the end of my nonfiction book, Hearing Maud. However, 2017 awaits, and Carol is such a marvelous writer that she has persuaded me, when gaps of time open, to plug them with poetry.

This is my second review for the Australian Women Writers Challenge.